Monday, October 30, 2006

Breaking News: Bush Administration Ignores Science!!!

Excuse the titular sarcasm. Anyway, I came across yet another report in the Washington Post confirming that the Bush administration has, once again, ignored scientific opinion in favor of political ideology. In this particular case, the administration has ignored recommendations to list endangered species. I posted this, not because it should come as a surprise to anyone, but to emphasize that, despite the opinion of some of the far left, scientists are not part and parcel with greater authority (more informally, "the man"), and may often oppose it. For more information on how scientists are involving themselves in environmental policy, especially since their opinions have been ignored, see the International Union of Concerned Scientists webpage.

Monday, October 23, 2006

The Good, the Bad, and the Confounding: Biological Response to Climate Change

Environmentalists are concerned that current and future climate change could adversely affect life on earth, causing many species to go extinct and dramatically altering the composition of ecosystems worldwide. In response to climate change, organisms may undergo ecological and/or evolutionary changes to avoid extinction. Ecologically, populations may shift their ranges to stay within an optimal climate envelope. For example, populations in Virginia might expand their range north to New England. Populations may also, simultaneously, adapt to changing climate by altering their optimal climate envelope. Rather than expanding into New England, organisms may stay in Virginia and become accustomed to South Carolina weather. In this post, I will discuss three recent scientific findings that weigh in on this matter.

First, the good news, sort of. A recent paper in Science examined a well-characterized species of fruit fly, Drosophila subobscura. D. subobscura is native to Europe, but invaded North and South America within the last 30 years. The genome of D. subobscura, like many other species, contains chromosomal inversions. The details are complex, but essentially, chromosomal inversions allow for gene complexes to be passed on intact from parent to offspring. Recall that, normally, the process of recombination breaks genes apart, such that every gamete (sperm and egg) is a unique combination of the maternal and paternal genomes. Researchers have known for many years that chromosomal inversions vary in frequency with latitude, a strong indication that they are associated with adaptation to local climate. In this paper, researchers took historical data on chromosomal inversion frequency and climate on all three continents where D. subobscura now lives. They found that, in less than three decades, chromosomal inversion frequencies shifted accordingly with changes in climate. For example, chromosomal inversions once found in Spain might now be found in France. The importance of this study is that 1) as we already knew, climate really is changing; 2) organisms have the ability to adapt; and 3) they can adapt fast and on a human time-scale.

Second, the bad news. If every organism could perfectly compensate for changing climate, then perhaps climate change wouldn’t have much impact on biology. Unfortunately, this simply isn’t the case. D. subobscura, like many other small organisms, is special in that generation times are short and population sizes are often large, two factors that are known to facilitate rapid evolution. In contrast, other organisms of have long generation times (e.g. all trees) and small population sizes, and may not perfectly adapt to changing climate. However, a study published in this month’s American Naturalist suggests that even small insects like D. subobscura may not be safe. Using physiological data from 65 insect species occupying many climates, researchers found that cold-adapted species grow more slowly in their optimal climate envelope than warm-adapated species in their optimal climate envelope. Even though natural selection allows some species to inhabit cold climate, it cannot fully compensate for thermodynamics. Extrapolating a bit, this study suggests that as warm-adapted species expand their range north (or to higher elevation) they will likely displace cold-adapted species that do not grow as quickly. This study only examined insects (which, along with flowering plants, make up the vast majority of earth’s biodiversity), so it remains to be seen whether similar patterns emerge in other taxa with differing behavior and physiology.

And finally, the confounding. Organisms are not merely adapted to abiotic factors such as climate, but to other organisms as well. A paper published Nature a couple years ago, reported on the results from experimental ecosystems containing 3 species of Drosophila and a parasitic wasp. The enclosed ecosystems had varying temperatures, thus mimicking climatic changes associated with latitude. The details are not important, but the take home message from the study was that optimal climate envelope did not accurately predict changes in species composition at different temperatures. They conclude, therefore, that biological communities may respond idiosyncratically to climate change, causing many species to be extirpated from large parts of their range, while others expand their range rapidly.

Together with other studies, these three papers confirm that natural selection is indeed rapid and potent, but not perfect. Also, ecological factors may confound our ability to predict and therefore mitigate adverse affects of climate change. Taken together, such studies demonstrate how basic biological research can inform (and complicate) decisions on important environmental issues, if politicians care to take notice.

First, the good news, sort of. A recent paper in Science examined a well-characterized species of fruit fly, Drosophila subobscura. D. subobscura is native to Europe, but invaded North and South America within the last 30 years. The genome of D. subobscura, like many other species, contains chromosomal inversions. The details are complex, but essentially, chromosomal inversions allow for gene complexes to be passed on intact from parent to offspring. Recall that, normally, the process of recombination breaks genes apart, such that every gamete (sperm and egg) is a unique combination of the maternal and paternal genomes. Researchers have known for many years that chromosomal inversions vary in frequency with latitude, a strong indication that they are associated with adaptation to local climate. In this paper, researchers took historical data on chromosomal inversion frequency and climate on all three continents where D. subobscura now lives. They found that, in less than three decades, chromosomal inversion frequencies shifted accordingly with changes in climate. For example, chromosomal inversions once found in Spain might now be found in France. The importance of this study is that 1) as we already knew, climate really is changing; 2) organisms have the ability to adapt; and 3) they can adapt fast and on a human time-scale.

Second, the bad news. If every organism could perfectly compensate for changing climate, then perhaps climate change wouldn’t have much impact on biology. Unfortunately, this simply isn’t the case. D. subobscura, like many other small organisms, is special in that generation times are short and population sizes are often large, two factors that are known to facilitate rapid evolution. In contrast, other organisms of have long generation times (e.g. all trees) and small population sizes, and may not perfectly adapt to changing climate. However, a study published in this month’s American Naturalist suggests that even small insects like D. subobscura may not be safe. Using physiological data from 65 insect species occupying many climates, researchers found that cold-adapted species grow more slowly in their optimal climate envelope than warm-adapated species in their optimal climate envelope. Even though natural selection allows some species to inhabit cold climate, it cannot fully compensate for thermodynamics. Extrapolating a bit, this study suggests that as warm-adapted species expand their range north (or to higher elevation) they will likely displace cold-adapted species that do not grow as quickly. This study only examined insects (which, along with flowering plants, make up the vast majority of earth’s biodiversity), so it remains to be seen whether similar patterns emerge in other taxa with differing behavior and physiology.

And finally, the confounding. Organisms are not merely adapted to abiotic factors such as climate, but to other organisms as well. A paper published Nature a couple years ago, reported on the results from experimental ecosystems containing 3 species of Drosophila and a parasitic wasp. The enclosed ecosystems had varying temperatures, thus mimicking climatic changes associated with latitude. The details are not important, but the take home message from the study was that optimal climate envelope did not accurately predict changes in species composition at different temperatures. They conclude, therefore, that biological communities may respond idiosyncratically to climate change, causing many species to be extirpated from large parts of their range, while others expand their range rapidly.

Together with other studies, these three papers confirm that natural selection is indeed rapid and potent, but not perfect. Also, ecological factors may confound our ability to predict and therefore mitigate adverse affects of climate change. Taken together, such studies demonstrate how basic biological research can inform (and complicate) decisions on important environmental issues, if politicians care to take notice.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

On Population Growth

Note: after starting this article a week ago, I quickly realized it could balloon into a book if I didn’t stop somewhere, so here a is brief, very incomplete examination of population growth and decline.

A news article in the June 30 edition of Science discussed declining birth rates, most pronounced in the developed world, and the prospect of population decline. Popular wisdom holds that environmentalists see population decline as unequivocally good, while economists see population decline as unequivocably bad. If both camps were correct, then population decline would be a zero-sum game: our environment benefits as our economy collapses. On the contrary, as I hope to demonstrate below, population decline can be a positive-sum game (both the environment and the economy win) with the correct policies in place. Reactionaries worried about population decline are largely motivated by politics, not economics. Second, I take a course-grained look at what factors, mainly economic well-being, may cause lower population growth and what they might have to say for our attempts to promote worldwide population decline.

Popular wisdom among environmentalists is that, caeterus parebus, population decline is unequivocably good for the environment – it would allow us to use less land for living, agriculture, and resource extraction. If nothing else, less people means less carbon dioxide emissions, which will help reverse climate change. I would like to investigate more specifics of this argument, and even read arguments to the contrary, but will put that off now and, for the purposes of this article, make the assumption that the popular wisdom is correct.

What about the economic impacts of population decline? Popular wisdom states that population decline is bad for the economy (GDP decreases, production drops, and expenditures on healthcare and penchants increase as the population ages). The Science article seems to more or less concur, quoting one demongrapher as saying:

It is not clear to me exaclty how common this view is among economists, as I will explain in more detail below, but it is does seem to be the common perception. For example, in a letter to the editors of Science, an ecologist said he would have expected such an article from Business Week or the Economist, but not Science (I guess he perceives that scientists alone possess a non-ideological opinion of what constitutes human well-being).

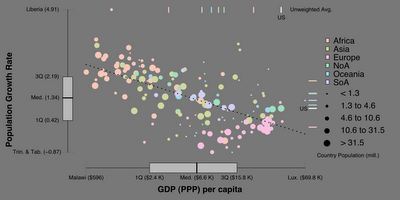

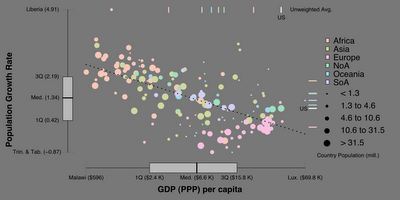

What policies can we pursue if we want to achieve population decline? People often cite that increased affluence causes lower birth rates via increased labor participation by women, access to controception, and delayed child bearing due to prolonged education and time spent working. For example, affluent countries, namely those in Europe, have many of the lowest birth rates in the world. To examine this claim more rigourously, I gathered two pieces of public data for most (178) countries: 1) GDP (PPP) per capita and 2) Population Growth rate. You can go to Wikipedia.org and find out more about these variables yourself, but briefly, GDP (PPP) per capita is a measure of average well-being, and population growth rate is population inputs (birth rate + immigration) minus outputs (death rate + emigration) divided by population size. Given the hypothesis that population growth decreases with increased affluence, one would expect a negative correlation between the two factors (actually, the inclusion of immigration and emigration confounds the analysis, but we will ignore that, as I doubt they change the overall pattern). I generated the figure below which demonstrates visually (and the statistics concur) that the hypothesis is correct. (There is a lot more information in this figure, including box and whisker plots of the two data sets along the axes, the overall population sizes of countries, and the continents to which countries belong.)

My initial reaction to the data was that African countries cluster towards the top left (low income, high population growth) and European countries cluster towards the bottom right (high income, low population growth/decline). The statisically minded observer might conclude that countries within a continent are not independent. Intuition bears this out, as, for example, it would not surprise anyone to hear that social, poltical, and economic ties between citizens of Germany and France may precipitate shared patterns of decision making.

To test this idea further, I carried out the same analysis above, but one continent at a time. The negative correlation between well-being and population growth was statistically significant in only one continent, Africa. Meanwhile, N. America, S. America, Asia, and Oceania showed no pattern. Surprisingly, Europe showed a significant, positive correlation (population growth increased with economic well-being). Consequently, the putatively strong, negative correlation between economic well-being and population growth rate may simply be a by-product of the high birth rates in poor African countries and the low birth rates in rich European countries. European and African countries differ in many respects and differences in birth rate may have nothing to do with economic well-being.

A quick caveat: I really have not “disproven” the hypothesis that increased affluence leads to population decline. Rather, I have merely provided some reasons to be skeptical. A better (and more time-intensive) analysis would be to look at change in economic well-being with change in population growth over time. Maybe I will do that in the future.

What does this all mean? If, as I have assumed, population decline is better for the environment, and greater affluence leads to decreased population growth, which may not be true, then the best environmental policy would be to promote economic growth, even if that development led to some environmental problems along the way (as the old adage goes, you have to break eggs to make an omelet). If, however, economic well-being has no effect on birth rates, then the two policies can be pursued independently. For example, we cannot simply hope that economic aid will be sufficient. Instead, we must promote other changes, such as increased access to contraception, in order to achieve the goal of reduced population growth.

Finally, I want to discuss briefly the putative economic collapse that will befall countries with declining birth rates. First of all, recall that the economic well-being of a country is not its gross GDP, but its GDP per capita. For example, China’s gross GDP is much greater than that of Luxembourg, but no one would say the average citizen of Luxembourg is worse off than the average citizen of China. However, one might notice that the political power of China is much greater than Luxembourg. Consequently, the politcians’ of a country might be apt to pursue a policy of population growth (as many European countries have) since it increases that country’s power. However, so long as per capita GDP does not decline, citizens of a country do not suffer from declining birth rates. To avoid declining per capita GDP, countries with falling birth rates may have to pursue some unpleasant policies, such as decreasing benefits to the elderly, increasing the retirement age, or increasing the tax burden on workers. However, done correctly, I don’t think such policies represent economic catastrophy. From my reading, magazines like the Economist concur, (in fact, I have borrowed many of my ideas from them), suggesting that actual economists do not conform to the perception held by those outside the discipline.

In conclusion, it seems that we can pursue economic and environmental well-being simultaneously, though we should be skeptical of claims that economic well-being always leads to decreased population growth. I am still unsure exactly how good population decline is for the environment, as well as the ultimate causes behind decreased population growth. Hopefully I can address those in the near future!

A news article in the June 30 edition of Science discussed declining birth rates, most pronounced in the developed world, and the prospect of population decline. Popular wisdom holds that environmentalists see population decline as unequivocally good, while economists see population decline as unequivocably bad. If both camps were correct, then population decline would be a zero-sum game: our environment benefits as our economy collapses. On the contrary, as I hope to demonstrate below, population decline can be a positive-sum game (both the environment and the economy win) with the correct policies in place. Reactionaries worried about population decline are largely motivated by politics, not economics. Second, I take a course-grained look at what factors, mainly economic well-being, may cause lower population growth and what they might have to say for our attempts to promote worldwide population decline.

Popular wisdom among environmentalists is that, caeterus parebus, population decline is unequivocably good for the environment – it would allow us to use less land for living, agriculture, and resource extraction. If nothing else, less people means less carbon dioxide emissions, which will help reverse climate change. I would like to investigate more specifics of this argument, and even read arguments to the contrary, but will put that off now and, for the purposes of this article, make the assumption that the popular wisdom is correct.

What about the economic impacts of population decline? Popular wisdom states that population decline is bad for the economy (GDP decreases, production drops, and expenditures on healthcare and penchants increase as the population ages). The Science article seems to more or less concur, quoting one demongrapher as saying:

Urban areas in regions like Europe could well be filled with empty buildings and crumbling infrastructures as population and tax revenues decline. it is not difficult to imagine enclaves of rich, fiercely guarded pockets of well-being surrounded by large areas which look more like what we might see in some science-fiction movies.

It is not clear to me exaclty how common this view is among economists, as I will explain in more detail below, but it is does seem to be the common perception. For example, in a letter to the editors of Science, an ecologist said he would have expected such an article from Business Week or the Economist, but not Science (I guess he perceives that scientists alone possess a non-ideological opinion of what constitutes human well-being).

What policies can we pursue if we want to achieve population decline? People often cite that increased affluence causes lower birth rates via increased labor participation by women, access to controception, and delayed child bearing due to prolonged education and time spent working. For example, affluent countries, namely those in Europe, have many of the lowest birth rates in the world. To examine this claim more rigourously, I gathered two pieces of public data for most (178) countries: 1) GDP (PPP) per capita and 2) Population Growth rate. You can go to Wikipedia.org and find out more about these variables yourself, but briefly, GDP (PPP) per capita is a measure of average well-being, and population growth rate is population inputs (birth rate + immigration) minus outputs (death rate + emigration) divided by population size. Given the hypothesis that population growth decreases with increased affluence, one would expect a negative correlation between the two factors (actually, the inclusion of immigration and emigration confounds the analysis, but we will ignore that, as I doubt they change the overall pattern). I generated the figure below which demonstrates visually (and the statistics concur) that the hypothesis is correct. (There is a lot more information in this figure, including box and whisker plots of the two data sets along the axes, the overall population sizes of countries, and the continents to which countries belong.)

My initial reaction to the data was that African countries cluster towards the top left (low income, high population growth) and European countries cluster towards the bottom right (high income, low population growth/decline). The statisically minded observer might conclude that countries within a continent are not independent. Intuition bears this out, as, for example, it would not surprise anyone to hear that social, poltical, and economic ties between citizens of Germany and France may precipitate shared patterns of decision making.

To test this idea further, I carried out the same analysis above, but one continent at a time. The negative correlation between well-being and population growth was statistically significant in only one continent, Africa. Meanwhile, N. America, S. America, Asia, and Oceania showed no pattern. Surprisingly, Europe showed a significant, positive correlation (population growth increased with economic well-being). Consequently, the putatively strong, negative correlation between economic well-being and population growth rate may simply be a by-product of the high birth rates in poor African countries and the low birth rates in rich European countries. European and African countries differ in many respects and differences in birth rate may have nothing to do with economic well-being.

A quick caveat: I really have not “disproven” the hypothesis that increased affluence leads to population decline. Rather, I have merely provided some reasons to be skeptical. A better (and more time-intensive) analysis would be to look at change in economic well-being with change in population growth over time. Maybe I will do that in the future.

What does this all mean? If, as I have assumed, population decline is better for the environment, and greater affluence leads to decreased population growth, which may not be true, then the best environmental policy would be to promote economic growth, even if that development led to some environmental problems along the way (as the old adage goes, you have to break eggs to make an omelet). If, however, economic well-being has no effect on birth rates, then the two policies can be pursued independently. For example, we cannot simply hope that economic aid will be sufficient. Instead, we must promote other changes, such as increased access to contraception, in order to achieve the goal of reduced population growth.

Finally, I want to discuss briefly the putative economic collapse that will befall countries with declining birth rates. First of all, recall that the economic well-being of a country is not its gross GDP, but its GDP per capita. For example, China’s gross GDP is much greater than that of Luxembourg, but no one would say the average citizen of Luxembourg is worse off than the average citizen of China. However, one might notice that the political power of China is much greater than Luxembourg. Consequently, the politcians’ of a country might be apt to pursue a policy of population growth (as many European countries have) since it increases that country’s power. However, so long as per capita GDP does not decline, citizens of a country do not suffer from declining birth rates. To avoid declining per capita GDP, countries with falling birth rates may have to pursue some unpleasant policies, such as decreasing benefits to the elderly, increasing the retirement age, or increasing the tax burden on workers. However, done correctly, I don’t think such policies represent economic catastrophy. From my reading, magazines like the Economist concur, (in fact, I have borrowed many of my ideas from them), suggesting that actual economists do not conform to the perception held by those outside the discipline.

In conclusion, it seems that we can pursue economic and environmental well-being simultaneously, though we should be skeptical of claims that economic well-being always leads to decreased population growth. I am still unsure exactly how good population decline is for the environment, as well as the ultimate causes behind decreased population growth. Hopefully I can address those in the near future!

Monday, October 09, 2006

Is recycling bad for the environment?

Yesterday I came across an article about the negative impacts of recycling (for a more entertaining version of essentially the same information, watch Penn and Teller’s Bullshit!) This is the kind of article that I hate to love. While thought-provoking, it gives me enough epistemological nightmares to reconsider having an opinion on anything. If recylcing isn’t good for the environment, what is?

The author, economist Daniel K. Benjamin, concludes from his research that, at best, recycling is a waste of money, and, at worst, adversely affects the environment. He cites ‘8 myths’ about recycling:

He counters these myths by arguing that there is ample and increasing land fill capacity which is, by the EPA’s own admission, environmentally safe; packaging actually saves resources; trash is a good which should be traded between states; we are not running out of resources (paper, aluminum, oil [here I would disagree]); recycling costs and pollutes more than making a new product; when it does save resources, private industry recycles without government incentive. For the most part, assuming his data are correct, I argee with Benjamin, though I am a bit skeptical because many of his citations come from the same few sources.

- “Our garbage will bury us”

- “Our garbage will poison us”

- “Packaging is our problem”

- “We must achieve trash independence”

- “We squander irreplacable resources when we don’t recycle”

- “Recycling always protects the environment”

- “Recycling saves resources”

- “Without forced recycling mandates, there wouldn’t be recycling”

Benjamin currently works for a think-tank called Property and Environmental Research Center (PERC), which advocates market based approaches to environmental problems. After having browsed their webpage, I have mixed opinions. On the one hand, they offer some salient advice. For example, they advocate letting National Parks manage their own finances, allowing them to charge consumers what their services really cost. This would enable the parks to stop losing money and protect resources degraded by overuse. On the other hand, they cite the Endangered Species Act as a failure because it has only rescued a small percentage of listed species. Obviously, they don’t know their biology. Check out the Science article I have posted below for one of many great responses to criticism of the ESA.

In conclusion, I am not sure what to think of recycling, Benjamin, or the PERC. While they smack of libertarianism, PERC raises some thought provoking points and even give Bush a bad rap for his environmental policy. The take home message is that seemingly simple issues like recycling can be quite complex. Hopefully, I can investigate further on this subject and eventually come to my own, well-informed opinion.

ESA.pdf

First Post

In the past, I have shied away from public writing because 1) there was already a glut of public, unedited information and 2) I didn't know enough to offer new or insighful commentary. The first hasn't changed, and for the most part, neither has the second. However, I am a bit bored at the moment. Anyway, after reading a story about eco-terrorism targeted at scientists in the magazine Nature, I felt compelled as both an environmentalist and future scientist to respond, but in a broader manner. Specifically, the article helped define and unite a series of on-going debates I have had with myself and friends. Essentially, are rationality, science, technology and market-based economics incommensurable with the goals of the environmental movement, which (in my observation) often appeals to emotion, primitivism and 'anti-capitalism'? In high school and early in college, I would have probably answered 'yes'. Having recently finished college, with a little more education under my belt, I am more skeptical and lean toward 'no'. With this blog, I hope to expound upon these ideas, and when time allots, bring forth empirical data to shine light on the murkier issues. Please feel free to respond with questions and criticism.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)