A news article in the June 30 edition of Science discussed declining birth rates, most pronounced in the developed world, and the prospect of population decline. Popular wisdom holds that environmentalists see population decline as unequivocally good, while economists see population decline as unequivocably bad. If both camps were correct, then population decline would be a zero-sum game: our environment benefits as our economy collapses. On the contrary, as I hope to demonstrate below, population decline can be a positive-sum game (both the environment and the economy win) with the correct policies in place. Reactionaries worried about population decline are largely motivated by politics, not economics. Second, I take a course-grained look at what factors, mainly economic well-being, may cause lower population growth and what they might have to say for our attempts to promote worldwide population decline.

Popular wisdom among environmentalists is that, caeterus parebus, population decline is unequivocably good for the environment – it would allow us to use less land for living, agriculture, and resource extraction. If nothing else, less people means less carbon dioxide emissions, which will help reverse climate change. I would like to investigate more specifics of this argument, and even read arguments to the contrary, but will put that off now and, for the purposes of this article, make the assumption that the popular wisdom is correct.

What about the economic impacts of population decline? Popular wisdom states that population decline is bad for the economy (GDP decreases, production drops, and expenditures on healthcare and penchants increase as the population ages). The Science article seems to more or less concur, quoting one demongrapher as saying:

Urban areas in regions like Europe could well be filled with empty buildings and crumbling infrastructures as population and tax revenues decline. it is not difficult to imagine enclaves of rich, fiercely guarded pockets of well-being surrounded by large areas which look more like what we might see in some science-fiction movies.

It is not clear to me exaclty how common this view is among economists, as I will explain in more detail below, but it is does seem to be the common perception. For example, in a letter to the editors of Science, an ecologist said he would have expected such an article from Business Week or the Economist, but not Science (I guess he perceives that scientists alone possess a non-ideological opinion of what constitutes human well-being).

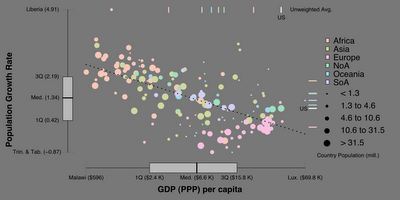

What policies can we pursue if we want to achieve population decline? People often cite that increased affluence causes lower birth rates via increased labor participation by women, access to controception, and delayed child bearing due to prolonged education and time spent working. For example, affluent countries, namely those in Europe, have many of the lowest birth rates in the world. To examine this claim more rigourously, I gathered two pieces of public data for most (178) countries: 1) GDP (PPP) per capita and 2) Population Growth rate. You can go to Wikipedia.org and find out more about these variables yourself, but briefly, GDP (PPP) per capita is a measure of average well-being, and population growth rate is population inputs (birth rate + immigration) minus outputs (death rate + emigration) divided by population size. Given the hypothesis that population growth decreases with increased affluence, one would expect a negative correlation between the two factors (actually, the inclusion of immigration and emigration confounds the analysis, but we will ignore that, as I doubt they change the overall pattern). I generated the figure below which demonstrates visually (and the statistics concur) that the hypothesis is correct. (There is a lot more information in this figure, including box and whisker plots of the two data sets along the axes, the overall population sizes of countries, and the continents to which countries belong.)

My initial reaction to the data was that African countries cluster towards the top left (low income, high population growth) and European countries cluster towards the bottom right (high income, low population growth/decline). The statisically minded observer might conclude that countries within a continent are not independent. Intuition bears this out, as, for example, it would not surprise anyone to hear that social, poltical, and economic ties between citizens of Germany and France may precipitate shared patterns of decision making.

To test this idea further, I carried out the same analysis above, but one continent at a time. The negative correlation between well-being and population growth was statistically significant in only one continent, Africa. Meanwhile, N. America, S. America, Asia, and Oceania showed no pattern. Surprisingly, Europe showed a significant, positive correlation (population growth increased with economic well-being). Consequently, the putatively strong, negative correlation between economic well-being and population growth rate may simply be a by-product of the high birth rates in poor African countries and the low birth rates in rich European countries. European and African countries differ in many respects and differences in birth rate may have nothing to do with economic well-being.

A quick caveat: I really have not “disproven” the hypothesis that increased affluence leads to population decline. Rather, I have merely provided some reasons to be skeptical. A better (and more time-intensive) analysis would be to look at change in economic well-being with change in population growth over time. Maybe I will do that in the future.

What does this all mean? If, as I have assumed, population decline is better for the environment, and greater affluence leads to decreased population growth, which may not be true, then the best environmental policy would be to promote economic growth, even if that development led to some environmental problems along the way (as the old adage goes, you have to break eggs to make an omelet). If, however, economic well-being has no effect on birth rates, then the two policies can be pursued independently. For example, we cannot simply hope that economic aid will be sufficient. Instead, we must promote other changes, such as increased access to contraception, in order to achieve the goal of reduced population growth.

Finally, I want to discuss briefly the putative economic collapse that will befall countries with declining birth rates. First of all, recall that the economic well-being of a country is not its gross GDP, but its GDP per capita. For example, China’s gross GDP is much greater than that of Luxembourg, but no one would say the average citizen of Luxembourg is worse off than the average citizen of China. However, one might notice that the political power of China is much greater than Luxembourg. Consequently, the politcians’ of a country might be apt to pursue a policy of population growth (as many European countries have) since it increases that country’s power. However, so long as per capita GDP does not decline, citizens of a country do not suffer from declining birth rates. To avoid declining per capita GDP, countries with falling birth rates may have to pursue some unpleasant policies, such as decreasing benefits to the elderly, increasing the retirement age, or increasing the tax burden on workers. However, done correctly, I don’t think such policies represent economic catastrophy. From my reading, magazines like the Economist concur, (in fact, I have borrowed many of my ideas from them), suggesting that actual economists do not conform to the perception held by those outside the discipline.

In conclusion, it seems that we can pursue economic and environmental well-being simultaneously, though we should be skeptical of claims that economic well-being always leads to decreased population growth. I am still unsure exactly how good population decline is for the environment, as well as the ultimate causes behind decreased population growth. Hopefully I can address those in the near future!

1 comment:

From my experience (as opposed to in depth research) economists see people as an input, much as land or capital are inputs. Therefore, in some sense, more people can be good for the economy, or more likely, neutral, since everyone produces (on average) what they consume (purely in a mathematical sense). The putative problem of population decline is really only a concern in Europe, Australia and Japan, where young people are net payers to the "system" (in that they work more, pay higher taxes, and use less services) and old people are net borrowers (work less, pay lower taxes, and use more services). That is why I argue that with proper policy changes, the negative impacts of population decline can be mitigated.

Another option is to permit more immigration, however this (supposedly) erodes the cultural fabric of the German, French, Dutch, or other peoples. Nonetheless, it is interesting that politicians promote policies that increase birth, so there are more laborers, but block immigration of young people who will "steal" jobs. It's pretty hard to conceive of how both statements could be true, and in fact, I think this whole mess of increasing birth rates is at best meant to preserve cultural heritage and at worst is thinnly veiled racism

Post a Comment